We’ve met Edward Pellew (1757 – 1833) on this blog before

(see link at end of article) and it’s probable that we’ll meet him again as he

ranks just below Nelson, and certainly with

Cochrane, as one of the Royal Navy’s most intrepid commanders during the

Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars. His earliest fighting experience came during

the American War of Independence when he was present at fighting on Lake

Champlain and his career was to culminate as Admiral Viscount Exmouth when he

commanded a combined British-Dutch squadron in operations against Barbary

pirates in Algiers in 1816. A humane and decent man, his personal courage was legendary

and although his career was studded with desperate naval actions one of his

most notable feats of heroism was not to be in a combat situation.

1795, the third year of the Revolutionary War, saw Commodore

Pellew commanding a squadron of frigates from his own HMS Indefatigable. Operating in the Western Approaches and off

North-Western Coast of France, Pellew’s force was to score significant success through

the year. By January 1796 however Indefatigable

had been brought into Plymouth for refitting. It was an opportunity for

Pellew to relax ashore on and 26th January he was on the way with his

wife to dine at the house of a well-known clergyman, Dr. Robert Hawker. As the Pellew arrived Hawker

ran out and called "Have you heard

of the wreck of the ship under the Citadel? " This was enough to send

Pellew racing to the scene of the disaster.

|

| The wreck of the Dutton by Thomas Luny Note group on beach, hauling on hawsers |

The ship involved was the Eastindiaman Dutton – and as such was manned by civilians. This vessel had been

underway for the West Indies with no less than 400 troops for the strengthening

of the garrisons there, together with a number of camp followers, not to

mention the ship’s own crew – the total on board was estimated at somewhere between 500

and 600. It is an indication of the extreme dependence upon weather conditions

during the Age of Sail that the Dutton

had already been seven weeks at sea but had been driven back to Britain by

adverse winds. Given the number of people crammed into a vessel less than 200

feet long it is not surprising that there should be a large number of sick on

board. It had now been driven against Plymouth Hoe, an open space that slopes

down towards the sea and on which the Citadel referred to by Dr. Hawker stands.

It ends at low limestone cliffs with a beach below.

|

| Edward Pellew |

Pellew arrived on the beach to find – one can imagine that

it was to his disgust – that most of the

Dutton’s senior officers had already abandoned ship. They had made it by

clinging to a single rope stretched between ship and shore. Others had also gained the shore but the process

was slow and dangerous – one eyewitness wrote that “you would at one moment see a poor wretch hanging ten or twenty feet

above the water, and the next you would lose sight of him in the foam of a wave”.

It was obvious that this method alone would be incapably of saving the hundreds

on board before the hull broke up. Despite Pellew’s exhortations to the ship’s

officers to return to the ship – and to each an offer of five guineas – they refused

to do so, as too did local pilots who believed that the case was hopeless. Pellew

realised that without his direction almost all on Dutton ship would be lost and he resolved to go out himself. He did

so by getting dragged to the ship by the single rope. This was hazardous, since

the vessel’s masts had collapsed towards the shore and he was at one stage

dragged under the mainmast, only extricating himself with leg and back-injuries

that were afterwards to confine him to bed. He did however finally reach the wreck

and took command – he made it plain that absolute compliance with his orders

would be essential and that he himself would be the last to quit the wreck. His

reputation as a national hero was already well established and his presence

alone did much to reduce any tendency to panic. A complication was however that

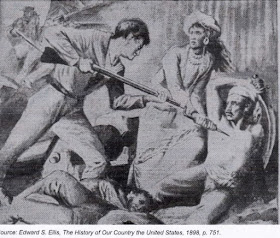

some of the soldiers had broken into the spirit store and were already drunk. Pellew, sword in hand, made it plain that that

he would have no hesitation in killing anybody exhibiting disobedience.

Back at HMS Indefatigable

it was not known that Pellew was on the Dutton

but efforts were made to get boats to her. Despite gallant attempts it proved

impossible to bring them alongside. More successful however was a small boat from

a merchant vessel. This was manned by a naval midshipman and by the merchant

vessel’s Irish mate, one Jeremiah Coghlan. With these men’s help Pellew managed

to get two more hawsers stretched from the wreck to the shore. Pellew set men to work to get cradles constructed

that could be slung beneath the hawsers to be pulled to and fro. In order to

avoid shock-loading of the hawsers as the wreck rolled, and to avoid the consequent

risk of their snapping, they were not made fast at the shore end. Each line was

instead held by a group of men who tightened and relaxed them so as to keep the

tension steady. This must have been exhausting and was not the least impressive

aspect of the entire rescue. Transfer by cradle now commenced but it was

obviously unsuited to the weak and vulnerable – a category that included one

three-week old baby on board. Coghlan in his small boat managed to get some 50

people to shore before any other craft reached the wreck.

While this was in progress a sloop and two large pulling-boats

had managed to reach the Dutton from

shore. In these the women children and the sick were landed, Pellew being adamant

in ensuring that order was maintained despite the soldiers’ drunkenness – he was

witnessed beating one looter with the flat of his sword. The handling of the rescue

boats in such conditions was an epic in itself and they were in due course to get

the soldiers to shore, followed by the ship’s company. Pellew was among the last

to leave – passing ashore along a hawser – and the battered hull broke up soon

afterwards. All on board had been saved.

|

| Coghlan in silhouette (Like Jane Austen's Captain Wentworth?) |

It is typical of Pellew that the only mention he made in the Indefatigable’s log was the statement “'Sent two boats to the assistance of a ship

on shore in the Sound” with no reference to himself. A pleasing postscript –

and a long one – was that Jeremiah Coghlan, the young civilian who had done

such heroic work in his small boat was to join the Navy and have an illustrious

career. Pellew took him on board the Indefatigable

as a midshipman and had him follow him when he took command of HMS Impetueux in 1799. Coghlan was given

command of the cutter HMS Viper the next

year and he was promoted further following a cutting-out operation, in which he

snatched the French gun-brig Cerbère

from a defended harbour. His subsequent career was to be the stuff of naval

fiction – single-ship actions, storming shore-batteries, seizing Naples in 1815.

When Pellew became Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, from 1811 Coghlan was to

be his flag captain on HMS Caledonia. One

of the heroes of the Age of Fighting Sail, he was to live long enough to see the

birth of the steam navy.

And Pellew? We’ll return to him again in the future.

Britannia’s Spartan

Six-inch breech loading guns represented the cutting edge of

naval technology in the early 1880s. In my novel Britannia’s Spartan they are shown in use in battle on both British and Japanese

ships. The splendid Japanese woodcut below shows Japanese crews managing just

such a weapon in the war of 1894-95 against China. Click on the image for further

details.