November 1st 2014 is the 100th anniversary

of the first defeat to be suffered by Britain’s Royal Navy in a century. It was

fought in stormy seas and fading light off the coast of Chile and was to result

in the loss of over 1600 men. The circumstances were dramatic in the extreme.

In an earlier blog (on August 1st) entitled

“Germany’s Doomed Nomads” I outlined how Imperial German Navy ships stationed

outside home waters at the outbreak of WW1 were in an unenviable position.

Germany possessed only one fortified naval base overseas – at Tsingtao in China

– and the various German colonies around the world – Togo, Cameroon, South-West

Africa, Tanganyika, Northern New Guinea and various Pacific island groups,

could provide only limited coaling and maintenance facilities. Tanganyika held

out until the end of the war but all other colonies were conquered by Britain

and her allies within the first year. As Tanganyika's coast was blockaded from the

beginning it could provide no facilities to support naval operations.

|

| The tragic HMS Good Hope |

|

| von Spee |

Germany’s main overseas naval force was the East Asia

Squadron, based in Tsingtao. Commanded in 1914 by Vice Admiral Maximilian,

Reichsgraf von Spee, its main strength lay in two modern armoured Cruisers, the

Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and four modern light cruisers, Dresden, Emden, Leipzig and Nürnberg.

There were also a number of gunboats and a single destroyer, mainly for

police-type actions along the coast of China. Impressive as this force might

seem, it was puny by comparison with the naval forces of Britain’s ally,

Japan, which not only deployed large

numbers of superb ships and manned them with seasoned professionals, but which

nine years before had achieved the greatest naval victory in history up to that

time. There were in addition British ships in the area, and the Royal

Australian Navy’s flagship, the battlecruiser HMAS Australia, was alone superior to von Spee’s entire squadron.

|

| SMS Leipzig - other German cruisers essentially similar |

When war broke out in August 1914 most of the warships of

the East Asia Station were dispersed at various Pacific island colonies on routine

missions. Von Spee recognised that Tsingtao could not be held indefinitely – the

Japanese declared war on Germany in August 23rd after which they joined

Britain in a blockade and siege of the base. Von Spee accordingly ordered his ocean-going

vessels to rendezvous at Pagan Island in the northern Marianas. In conference with

his commanders there he planned, probably with little expectation of success, a

return voyage across the world to Germany. The key factor would be coal supply by chartered

colliers, which would have to meet the squadron at various points, their movements

being coordinated by radio. Organising this, and making it happen operationally

in the teeth of massive sweeps by the British and Japanese, was likely to be

difficult in the extreme. The Emden was detached to conduct a separate

– and very successful – campaign in the Indian Ocean. Von Spee was starved of

news as all German undersea cables through British controlled areas had been

cut, and radio capabilities were still very limited. The Nürnberg

was therefore dispatched to Hawaii – neutral territory – to gather war news. Von

Spee headed for German Samoa with Scharnhorst

and Gneisenau, then east, towards the

French possession of Tahiti, where they made a brief bombardment. Reunited, the

squadron coaled at Easter Island from German colliers.

|

| SMS Gneisenau, identical to her sister Scharnhorst, in pre-war ochre and white livery |

An obsolete cruiser SMS Geier,

failed to make the rendezvous at Pagan, and had to intern herself at then-neutral

Hawaii because of technical problems. Left behind at Tsingtao were four small

gunboats Iltis, Jaguar, Tiger, Luchs and

the torpedo boat S-90. This latter

craft was to score a significant success by torpedoing and sinking the old

Japanese cruiser Takachiho on October

29th. All these craft were scuttled prior to surrender of Tsingtao

to the British and Japanese in November.

|

| SMS S-90, Nemesis of the old Japanese cruiser Takachiho |

The British Admiralty made destruction of von Spee’s

squadron a high priority. The futile German bombardment of Papeete, Tahiti, and

the destruction of an old French gunboat there (wasting ill-afforded ammunition

in the process) led the British to concentrate the search in the Western

Pacific. This seems very unwise in retrospect since Japan, Britain’s ally, already

had substantial forces in this area and British units could have been more gainfully employed further east. (Hindsight is always of course 20/20). It was only in early October that an

intercepted radio message indicated that von Spee was heading for the west

coast of South America to destroy British merchant shipping there.

|

| Good Hope, soon after commissioning Drawing by the eminent marine artist William Lionel Wyllie |

|

| Good Hope in wartime grey |

The British squadron sent into the Pacific from the South

Atlantic to counter such a move was almost wholly made up of obsolescent or

poorly-armed vessels, crewed by inexperienced naval reservists (echoes here of

the Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue disaster covered in my blog of September

19th). The force commanded by Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock

consisted of the near-obsolete armoured cruisers Good Hope (flagship), and Monmouth,

the modern light cruiser Glasgow and a

weakly-armed converted liner, the Otranto.

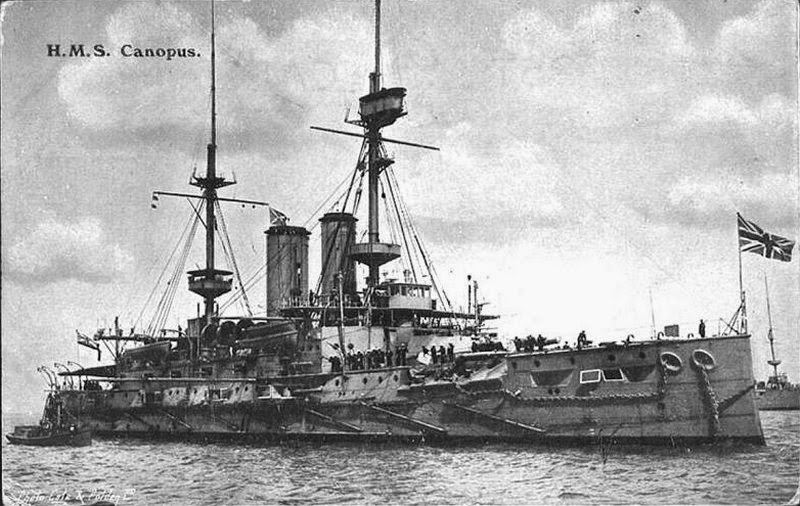

For heavy back-up Cradock was assigned the old, slow, but powerfully-armed

pre-dreadnought Canopus. In the event

her worn-out machinery made it impossible, despite heroic efforts by her

engine-room crew, to keep pace with the cruisers.

Except for two individual 9.2-inch turret-mounted guns on Good Hope, and four 6-inch mounted on Monmouth in double-gun turrets, the remaining twenty-six 6-inch weapons carried by the armoured cruisers

were positioned in casemates built into the sides of the hulls. Some

of these casemates were “two-storey” ones, with weapons in the lower positions inoperable

in any significant seaway. This made a substantial portion of the armament

essentially unusable and, as the weakness was so obvious, one wonders why naval

architects persisted with this feature through successive design classes.

|

| Monmouth - note the "two-storey" casemates for 6-in weapons |

By contrast, von Spee’s armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau each carried four 8.2-inch weapons in double-gun turrets

and each ship’s six 5.9-inch weapons, though casemate-mounted, were higher

above the waterline than on the British ships. The German 8.2-inch weapons were

markedly superior as regards range and firepower and both vessels had proved

themselves as “crack gunnery ships” in peacetime firings. Add to this the

superior German armouring and Cradock’s force can be seen to have been wholly

outmatched. Though the light cruiser Glasgow

was a superb new vessel, and individually superior to any one of her German

counterparts, she was outnumbered by Dresden,

Leipzig and Nürnberg.

The weakness of Cradock’s force was recognised, but the Admiralty

seems to have placed excessive trust in the presence of the Canopus and the four 12-inch guns of her

main armament. Cradock was told to use Canopus

as "a citadel around which all our

cruisers in those waters could find absolute security".

|

| Cradock |

It is notable that both Cradock and von Spee were largely

similar personalities – decent and

honourable men who shared the same enthusiasm and dedication to their

profession and who would have been good friends in other circumstances. There

was a chivalry and delicacy about both of them that belonged to an age which had

even by then almost disappeared. The Royal Navy was Cradock’s whole life – he

never married – and he had said that his preferred death would be either in a hunting

accident or during action at sea. A quote from book he wrote in 1908, “Whispers

from the Fleet,” describes the operations of a cruiser squadron in near-poetic

terms and prefigures, uncannily, the actual death which was to be so close to

that he wished for:

"The

Scene: - A heaving unsettled sea, and away over to the western horizon an angry

yellow sun is setting clearly below a forbidding bank of the blackest of wind-charged

clouds. In the centre of the picture lies an immense solitary cruiser with a

flag – ‘tis the cruiser recall – at her masthead blowing out broad and clear

from the first rude kiss given by the fast rising breeze. Then away, from half

the points of the compass, are seen the swift ships of a cruiser squadron all

drawing into join their flagship: some are close, others far distant and hull

down, with nothing but their fitful smoke against the fast fading lighted sky

to mark their whereabouts; but like wild ducks at evening flighting home to

some well-known spot, so are they, with one desire, hurrying back at the behest

of their mother-ship to gather around her for the night."

In late October both the British and German forces were close

to the coast of Chile, von Spee off Valparaíso and Cradock further south, but no

contact had yet been made. Glasgow

entered the Chilean port of Coronel to collect messages and news from the

British consul. She found there a German supply ship which promptly radioed

news of her arrival to von Spee. In line with the laws of neutrality Glasgow could take no action in port against this vessel and she left Coronel to rejoin Cradock. On

receipt of the news von Spee headed south to run down Glasgow. Alerted

by German radio-traffic (the importance of radio silence does not appear to

have been yet appreciated) Cradock turned north to meet the Germans, leaving Canopus far behind and Glasgow steaming south to join him.

The squadrons were now on a collision course and given the

disparity in forces Cradock’s decision to advance seems almost inexplicable,

the more so since he would lack Canopus’s

support. It was said later that he was "constitutionally incapable of

refusing action". Another explanation is that, knowing his mission was

impossible, Cradock wanted to damage von Spee’s ships and to force him to use

ammunition he could not replace, so making them easy targets for other British forces which would follow.

|

| Canopus - heavily armed but too slow to support Cracock |

Glasgow joined Good Hope, Monmouth and Otranto

early on November 1st, in seas too rough to allow human inter-ship transfer, messages

being sent across by line instead. In early afternoon Cradock deployed his

ships in line of battle and at 1617 hrs the German squadron sighted British

smoke. Von Spee took Scharnhorst,

Gneisenau and Leipzig ahead,

leaving the slower Dresden and Nürnberg to follow.

Confronted by this overwhelming force Cradock ordered a turn

away so that both squadrons rushed south in a chase that was to lasted 90

minutes. The slow, 16 knot, Otranto

was now Cradock’s millstone and he knew that he must choose between abandoning

her and continuing to run south with Good

Hope, Monmouth and Glasgow or to stand

and fight to protect the useless converted liner. Cradock decided he must

fight, and drew his ships closer together, turning to the south-east to close

with the German vessels while the sun was still high. He also ordered the Otranto, which was too weakly armed to influence the outcome, to escape west at full speed. Von Spee, meanwhile, was

manoeuvring his force to ensure that the British ships to the west would be

outlined against the setting sun.

|

| Sharnhorst in action - note rough sea |

Von Spee responded to Cradock’s manoeuvre by turning his own

faster ships away, maintaining the distance between the forces at 14,000 yards as

they steamed inparallel. At 1818 hrs, with

little daylight left, Cradock again tried to close, but von Spee once more turned

away to open the range. The sun set at 1850 hrs and the British ships were now

silhouetted against the last light in the west.

Von Spee closed the range to 12,000 yards and opened fire.

What followed was a massacre. The British 6-in weapons were

outranged by the German 8.2’s and when Cradock made another attempt to close

the German fire became even more devastatingly accurate. By 1930 hrs both Good Hope and Monmouth were on fire, and easy targets for the German gunners now that

darkness had fallen, whereas the German ships were shrouded in darkness. Monmouth’s guns fell silent but Good Hope continued firing until 1950

hrs when she too ceased fire, then exploded and disappeared. Scharnhorst maintained a merciless fire

on Monmouth, while Gneisenau joined Leipzig and Dresden in engaging

Glasgow. The Glasgow was still relatively undamaged but her captain turned away

to escape in the darkness, recognising that continuing the battle would be

futile.

.jpg) |

| Glasgow - Cradock's most modern ship |

Monmouth, badly

damaged, but still afloat, tried to run eastwards to beach herself on the Chilean

coast. The Germans lost her temporarily in the darkness but the Nürnberg, the slowest of von Spee’s

ships, was to find her. The German

captain directed his searchlights on to Monmouth’s

ensign in an invitation to surrender but she refused to do so. Nürnberg then opened fire reluctantly and

sank her. Aware that Canopus might be

somewhere in the vicinity von Spee turned north and the action ended.

All battles are horrible but Coronel seems particularly ghastly.

The rough seas, the all but impotent British armoured cruisers being pounded

with salvo after salvo, the darkness, the raging fires, Good Hope’s explosive end, the hope raised on Monmouth that she might yet survive, only to have it dashed, all

combine to give the encounter a nightmare quality. There were no survivors from

either Good Hope or Monmouth, 1,600 British officers and men,

including Cradock, having been killed. Glasgow and Otranto both escaped, neither with fatalities. Two British shells,

both duds, hit Scharnhorst, and four

shells struck Gneisenau. Three German

seamen were wounded. The greatest loss to von Spee was the expenditure of

ammunition which could not be replaced. When they next faced British ships, as

they would a month later, the German squadron would do so with depleted

magazines.

|

| von Spee's squadron in Valpariso Nov. 3rd 1914 There also appear to be Chilean ships present, nearer the camera |

Von Spee was aware that his victory would not be enough to

save his squadron, far from home as it was and without German bases between.

When, two days later, his squadron entered Valparaiso to the cheers of the

German residents, he refused to join in the celebrations. Presented with a bouquet

of flowers, he remarked "These will do nicely for my grave".

The defeat at Coronel, the first surface action in over a

century which the Royal Navy had lost, was both shocking and unexpected. Only

by swift and total annihilation of von Spee’s squadron could the humiliation be

avenged. Massive forces were sent south from Britain to ensure this – as they did

a month later.

But that’s a different story!

.svg.png)