When thinking of the ocean-going navy of the Southern

Confederacy in the American Civil War the image immediately comes to mind of

fast, largely unarmoured vessels such as the Alabama and the Florida,

general similar in construction terms to commercial vessels, albeit

strengthened to carry heavy armament. The corresponding image of a Confederate

ironclad is, by contrast, an armoured, improvised, steam-propelled raft

intended for service in rivers and coastal waters. It is therefore somewhat of

a surprise to learn that the Confederacy’s last “Blue-Water” naval vessel was a

heavily-armed ironclad, well capable of sinking any major Union warship she

encountered. Completed late in the Civil War, only the end of the conflict brought her potentially devastating career in Confederate service to an end only

just as it was starting. This was however to be just the prelude to spectacular

battle-service in a newly created navy on the other side of the world.

|

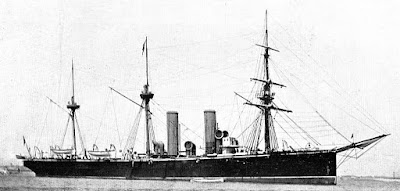

| CSS Stonewall |

The ship that was to

become the CSS Stonewall was one of

two ironclads constructed in France, personal approval for the project being

given in 1863 by the Emperor Napoleon III, who was sympathetic to the

Confederate cause. The objection that French neutrality would be compromised by

delivery of warships to either the Union or to the Confederacy was neatly

side-stepped by circulation of the rumour that they were intended for delivery

to the Khedive of Egypt – the appropriate names of Sphynx and Cheops were

allocated to them. A further element of confusion was added by ensuring that

the armament would come from Britain. The seagoing ironclad concept was a new

and revolutionary one at the time – France’s Gloire and Britain’s HMS Warrior,

the first of the type, had been launched in 1859 and 1860 respectively – so the

Confederacy was betting on acquiring cutting-edge naval technology.

|

| Armouring of Cheops and Sphynx - note waterline belts and armoured redoubts for and aft |

Sphynx and Cheops were of 1358 tons and some 190

feet long. Their 1200-hp steam engines, driving two screws, gave a top speed of

over 10-knots. Twin rudders made for very tight turning circles – a decided

advantage at a time when combat was likely to be at very close range. They also

carried an auxiliary sail rig – especially valuable for conservation of coal

when operating over long distances. The most notable feature was however the

heavy armour protection – a waterline belt with thickness ranging from 3-5 to

5-inches or iron, as well as some 5-inches on the redoubts fore and aft in

which the armament was housed. These latter structures were not rotating

turrets, but rather protective casemates from which the guns fired through

ports. As such they could be regarded as precursors of the later “central

battery” type of ironclads, as compared with the traditional broadside

arrangement of the earlier Gloire and

Warrior. Sphynx

and Cheops each carried a single 300-pounder

muzzle-loading Armstrong forward, firing over the pronounced ram-bow, with two

68-pounder weapons in the after redoubt. As such they were built to absorb

tremendous punishment as well as to deal it out.

|

| Sail Plan of Cheops and Sphynx - note armouring above ram. Note also how the weapons are carried high behind thick armour, |

The vessels were constructed in Bordeaux, on France’s

Atlantic coast, and were launched early in 1864. Human greed is however a major

obstacle to keeping a project of this sort secret. In this case the subterfuge about purchase by Egypt was exposed by a clerk at the shipyard who supplied information on the deal –

and hard evidence, in the form of documentation – to the United States

ambassador in Paris. With a diplomatic

crisis about neutrality brewing, the French Government had no option but to

block the sale. A new customer was immediately available however. Prussia’s

“Iron Chancellor”, Otto von Bismarck, supported by the Austro-Hungarians, had

precipitated war with Denmark. Heavily outnumbered, the Danish resistance was

fierce, heroic and doomed. The bright spot for Denmark was the performance of

its navy, both in support of land operations and on the open sea. (My blog of 8th January 2016

regarding the Battle of Heligoland refers. It can be found via the sidebar).

It was accordingly inevitable that both the Danes and their enemies should be

looking to purchase more warships. Sphynx

and Cheops would fit the bill to

perfection. In a cynical deal in which a sale to one side was balanced by a

sale to the other, the Sphynx was

sold to Denmark – and renamed Stærkodder

– while the Cheops was purchased by

Prussia and called Prinz Adalbert.

Thus were neutrality concerns elegantly sidestepped!

|

| Denmark's day of glory - the Nils Juel at Heligoland, 9th May 1864 |

A Danish crew arrived in Bordeaux in June 1864 to start

acceptance trials and take her to Denmark thereafter. (One wonders if there

were any embarrassing encounters with a Prussian crew arriving to take over Prinz Adalbert!). The war was however

winding down – with Denmark comprehensively beaten – and by 1st

August a preliminary peace treaty had been signed. By the time Stærkodder arrived in Copenhagen all was

over and she was by now essentially surplus to the requirements of the

vanquished nation.

Confederate agents had however followed the Sphynx/ Stærkodder affair with interest

and were still determined to acquire her. Negotiations – which must have

required a high degree of secrecy – resulted in a sale by Denmark and in early

January 1865 a Confederate crew commanded by Captain Thomas Jefferson Page (1808

– 1899) took delivery. The ship was commissioned at sea as the CSS Stonewall.

These events had not gone unnoticed by Union agents and

diplomats and once intelligence was obtained of the Stonewall’s “breakout” from the Baltic to the North Sea, and on to the

Atlantic, powerful Union Navy units were despatched to find and sink her. There

are strong parallels with the breakout of Germany’s battleship Bismarck

in 1941 and her hunting by Royal Navy forces. Among the Union ships deployed

were the steam-sloop USS Kearsarge –

recently the victor of her duel with the CSS Alabama off the French coast – and her sister USS Sacramento, supported later by the

steam-frigate USS Niagara. Though Kearsarge had been partly protected by

improvised chain-armour, all these ships would have been at a decided – and

perhaps fatal – disadvantage in any duel with the heavily-armoured Stonewall.

Once at sea the Stonewall

developed a leak – it is notable that her now-Prussian sister Prinz Adalbert deteriorated so rapidly

that she was taken from service in 1871 – and she put in at Quiberon, on

France’s Brittany coast, where repair possibilities see to have been limited,

and to take on supplies and further crew members. It is likely that many of

these recruits were not American, as was the case also with other Confederate

raiders, but men of other nationalities who were attracted by pay and by the

opportunity for adventure. Stonewall

now pressed on to Ferrol, in North-West Spain, where she could undertake

repairs. She remained there for almost two months. Word of her presence spread

and the USS Sacramento and USS Niagara took up station outside. (One is

reminded of HMS Shannon lying off

Boston in 1813, daring the USS Chesapeake

to come out).

|

| Portuguese battery at Belem fort firing warning shots to restrain USS Niagara. Common sense prevailed a and the situation was defused |

When the Stonewall

did finally emerge from Ferrol on 24th March, the Union warships

waiting for him declined to engage – wisely, in view of the disparity in

armament and armour. Captain Page now

headed for Lisbon, Portugal, to take on coal prior to a dash across the

Atlantic to attack Port Royal in South Carolina, the supply base for the Union

General Sherman's army. The Stonewall

was followed into port by the Sacramento

and Niagara – which under neutrality rules

could only glower at each other in enmity. An attempt by the Niagara to shift her berth was

interpreted by the Portuguese authorities as a potentially hostile move against

the Confederate vessel and warning shots from cannon on the castle of Belem put

an end to the manoeuvre. Formal neutrality rules – demanding that enemy ships

could not leave harbour simultaneously – were strictly applied and the Stonewall slipped away unmolested.

Time was running out for the Confederacy however. On 9th April

Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to Grant and on 26th April the

only other major Confederate force was surrendered by Johnson to Sherman. By

the time that Page and the Stonewall

put in at Nassau, in the British possession of the Bahamas, on 6th

May the epic conflict was at an end. The ironclad and her crew were now

orphans.

Page now decided to take his ship to Havana, in Cuba, then

still a Spanish possession. He handed her over to the government authorities there

against a payment of $16,000 and paid off her crew. The Spanish in turn handed

the Stonewall to the United States in

return for a similar payment.

The triumphant Union now possessed one of the most powerful

warships afloat, but in the aftermath of the Civil War there was little

appetite for retention of a large navy – the concern was indeed to run down one which had grown to gigantic

levels during the conflict. The Stonewall

lay decommissioned at the Washington Navy Yard for some two years until it was

decided to sell her.

And the buyer?

Opened up to foreign contact only thirteen years before, the

Empire of Japan was engaged on a furious, and historically-unprecedented,

campaign of modernisation. Its ambitions were all but boundless and acquisition

of an effective navy was of the highest priority. The ex-Confederate ironclad

would be ideal for their purposes.

The Stonewall

would be heading east, and under a new name - Kōtetsu - would embark on the most active

part of her career.

I’ll tell about that in the second part of this article, which

will appear soon. Watch out for it!

Download a free copy of Britannia’s Eventide

To thank subscribers to the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list, a free, downloadable, copy of a new short story, Britannia's Eventide has been sent to them as an e-mail attachment.

.jpg)