In

“Britannia’s Wolf”, first book in my

“Dawlish Chronicles” series, a key role is

played by the heavily-armed Ottoman Turkish coast defence ship

Mesrutiyet, which had been constructed

in Britain and whose two sisters were taken into Royal Navy service in 1878 as

HMS

Belleisle and HMS

Orion. These were some of the last coast defence

ships equipped with masts and yards, though in practice they do not appear to

have operated under sail.

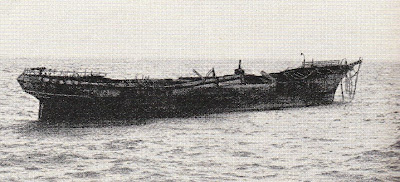

.jpg) |

Mesrutiyet – designed

for defence of the Turkish Straits and Black Sea coast

|

Coast defence

ships represented major components – in some cases the backbone – of minor

navies in the period 1870 to 1920, and in some cases beyond. Some few such

ships could also be found in larger navies.

They were specifically designed for operations close to the home

nation’s coast and were intended to act in cooperation with light

forces and to make maximum use of the shelter of fortified harbours and coastal

batteries. They carried a heavy armament for their size and were slow and usually

– with the exception of Netherlands ships – with limited range capability. They

were frequently designed with specific local conditions in mind – e.g. shallow

draughts to permit inshore manoeuvring. Shipboard accommodation and storage

requirements were limited as they could fall back on the resources of shore

bases. They varied in size from around 1,500 tons to 8,000 tons.

Navies with

coastal defence ships serving as their main capital ships tended to be those

which by size or location were focussed on defence of its own territory rather

than projection of force elsewhere. These included the Scandinavian countries,

the Netherlands (including its East Indian Empire) and Thailand. Germany also

built such ships in the years prior to Kaiser Wilhelm II and Admiral Tirpitz

embarking on construction of a navy to match that of Great Britain.

Larger navies

did however also employ some such ships to meet satisfy specific local

requirements. Russia, for example, built

several such ships for inshore operations in the Baltic. France did so to

provide additional and flexible support to fortified naval bases such as Brest and Toulon. British colonies in India and Australia built

several such ships for defence of key harbours.

Some examples

of coast defence ships from their birth in the1870s to their final demise in

the WW2 period are provided below.

Great

Britain

HMS Glatton (1871)

+No.2.JPG) |

| HMS Glatton in her Victorian glory - black hull, white superstructure |

The Glatton was designed for

"the defence of our own harbours and roadsteads, and for attacking those

of the enemy". In reality, her lack of freeboard would appear to have

precluded any operations whatsoever except those in calm weather and smooth

water. She carried her main armament of two 12” muzzle-loaders in a single

turret and there was in theory be no point on the

horizon to which at least one gun could not point, whatever the ship’s orientation.

To achieve this the superstructure was very narrow, so that at least one of the

guns in the turret could fire on targets to the after aspect of the ship. Blast

effects on the superstructure from firing abaft the beam were not taken into

account – or probably even understood at the time. The Glatton was the best protected ship of her day, with some 35% of

her 4900 tons displacement devoted to armour.

Generally

similar low freeboard ships, though with two turrets, were built for harbour

protection in India (HMS Abyssinia

and HMS Magdala) and for Australia

(HMS Cerebus). Thereafter the

coast-defence ship fell out of favour in the Royal Navy, as its raison d’etre

was not just local protection of British possessions but its ability to operate

on a global scale. Cost defence vessels were not to figure again in the Royal

Navy until World War 1. The jump in capability since the 1870s was a large one.

HMS Glatton and HMS Gorgon

(1918)

|

HMS Glatton in 1918

|

Britain’s need

to deliver heavy naval fire on German positions on the Belgian Coast during

World War 1 led not only to development of the modern monitor but to a search

for vessels from elsewhere which were suited to shallow-water operations. Two apparently

ideal coast defence ships had been under construction in Britain for the Norwegian

Navy and they were acquired in 1914, although they did not enter service until

1918 due to the need for modifications in the light of war experience. Now

called Glatton and Gorgon, and of 5746 tons, these ships

carried two 9.4” and four 6” guns, plus smaller weapons. They were slow (12

knots maximum) but heavily armoured and “bulged”, as shown below, to provide

protection against torpedo attack.

|

HMS Glatton in drydock, 1918. Note the anti-torpedo bulges.

|

In practice

neither ship lived up to its promise, Glatton

being destroyed by an accidental internal explosion in Dover Harbour in 1918

and Gorgon saw only limited action

before the war ended, She was later expended as a target ship.

France

Tonnerre (1877)

|

Tonnerre at sea – her turning circle was smaller than that of any other in the

French Navy

|

With the

success of British blockades of French naval bases in previous wars in mind, France

in the 1870s and 1880s made significant investment in slow, heavily armoured

and well-armed coast defence ships which

capable of deterring or breaking future blockades. The Tonnerre,

laid down in 1873 but not completed until 1879, represented a model for a

number of such vessels. With her displacement of 5765 tons and armament of two

10.8” turret-mounted guns the similarity to the HMS Glatton of the same period is striking.

Jemappes Class(1890)

Even larger coast-defence ships were built by France in

the 1890s, typical of these being the Jemappes

and Valmy of 1890.

.jpg) |

The Jemmapes: Note the 13.4” weapons fore and aft and the curiously

curves bow and stern profiles so typical of French cost-defence ships of the

period

|

These were

large ships – 6476 tons and their main armament of two 13.4” guns would have

made them very dangerous opponents in the waters close to the well-defended French bases.

Russia

Admiral Ushakov Class (1893)

|

Admiral Seniavin of the

Ushakov class

|

Though it

became fashionable in the Soviet period to ridicule the voyage of the Russian

Baltic Fleet to the Far East in 1904-05, and its subsequent massacre at the

Battle of Tsu-Shima, the achievement of getting such a large fleet half-way

across the world, without possessing naval bases on the way, was a very

impressive one. This was especially so

in the case of the three Ushakov coast defence ships – Admirals Ushakov, Seniavin and Apraksin – which had been designed for short-range

Baltic operations, primarily for operations against the Swedes should the

circumstances demand. These three vessels were essentially “pocket battleships”

long before the term was invented. On 4971 tons these vessels carried four

(Aprakzin carried three) 10” and four 4.7” guns. Seniavin and Apraksin

surrendered to the Japanese after Tsu-Shima, though they were returned to

Russia when both countries became uneasy allies in WW1 but Ushakov was sunk in the action.

The

Netherlands

The Royal Netherlands Navy employed their "armoured ships" to defend their overseas empire, especially

the country's vast colonial possessions in the East

Indies (modern Indonesia). Though essentially cost-defence vessels they had to be

capable of long-range cruising in view of the enormous distances involved when operating offshore of what is now Indonesia, of provision of artillery support during

amphibious operations, and with capacity for carrying the troops and equipment

needed in such operations. They also had to be armed and armoured well enough

to face contemporary armoured cruisers of the Japanese Navy (the Netherlands'

most likely enemy in the Pacific). As such they were expected to act as

mini-battleships rather than strictly as coastal defence vessels. Meeting this

combination of requirements was an almost impossible one.

Jacob van Heemskerck(1906)

Some nine

such ships were built in the 1890s and early 1900s and the last of these, the Jacob van Heemskerck reflected the

lessons learned from earlier ships.

.jpg) |

Jacob van Heemskerk with what may be the coast defence ship Piet Hein (1894) moored astern

|

Though constructed at the same time as HMS Dreadnought, and with the Japanese navy

about to build its own dreadnoughts, the Heemskerk,

with her main armament of two 9.2” weapons on 4920 tons displacement, and her

maximum speed of 16.5 knots, looked like a throwback to an earlier age. It is difficult to envisage circumstances in

which she could have offered any meaningful opposition to the Japanese and she

seems at this remove to be a sad example of money badly spent. She ended her

days as a German floating anti-aircraft battery in WW2.

Sweden

Äran Class

(1902)

Coast defence

ships represented the core of the Swedish Navy up to 1947. Between 1890 and

1905 some 11 vessels of considerable sophistication, and of careful reflection

of local needs, joined the fleet. It was

such vessels that Russia’s Admiral Ushakov

class were designed to combat in Swedish coastal waters. The Swedish ships were

relatively small, with limited speed, shallow draft, and very heavy guns

relative to the displacement. They were designed for close in-shore work along

the shores of Sweden and, if necessary, Finland. The aim was to outgun any

ocean-going warship of the same draft by a significant margin, making it a very

dangerous opponent for a cruiser, and deadly to anything smaller. The limitations

in speed and seaworthiness were a trade-off for the heavy armament carried.

Vessels similar to the Swedish ships were also built and operated by Denmark

and Norway, which had comparable requirements.

|

Äran (1902) – photographer

unknown, source http://www.merbil.se/marint.htm

|

A typical

Swedish coast defence vessel of 1902 was the Äran, one of a class of four vessels. As initially constructed

these 3592-ton vessels carried two 8.3” and six 6” weapons as well as two 18”

torpedo tubes. Three of this class, including Äran, were extensively upgraded and saw service until 1947.

Sverige Class (1912 – 1922)

|

Sverige during WW2 - Source photograph No. Fo200277 from Swedish National

Maritime Museum

|

The three

ships of this class can be argued to be the most effective coast defence vessels ever built. Though

designed before WW1, their completion was delayed, even though Sweden was neutral,

and at 7775 tons they were the largest ships taken into Swedish service.

Capable of some 23 knots and turbine powered, these vessels packed a very

potent punch of four 11.1” and eight 6” guns, plus, later, numerous anti-aircraft

armament. All three vessels were extensively modernised in the 1930s and helped preserve Sweden’s neutrality in WW2. Though well-armed they would have been too small, too cramped, too slow

and without enough range to engage enemy heavy ships in open water but if

handled properly in defence in their home shores they would probably have

presented a major challenge for any aggressor.

Norway

Eidsvold

Class (1900)

Launched in

1900 the two vessels of Norway’s Eidsvold-class

were very similar to Sweden’s Äran class. The most remarkable aspect of the Eidsvold’s and Norge’s careers was that they met their ends together when the

Germans invaded Norway in April 1940. German destroyers trapped both ships in the

fjord at Narvik on April 9th and demanded surrender from the senior

officer present, Captain Odd Isaachsen Willoch of the Eidsvold. A German officer boarded and tried to talk Willoch into

surrender, but was turned down. As he left the deck of Eidsvold, the German fired a red flare, indicating that the Norwegians

wished to fight. The battle-ready German destroyers torpedoed Eidsvold before she could fire her guns.

Eidsvold was blown in two and sunk in

seconds, propellers still turning. Only six of the crew were rescued, while 175

died in the freezing water. It was hardly a victory that the German Navy could be proud of.

|

Norge in happier times

|

Meanwhile,

deeper inside the fjord, Norge’s crew

heard explosions but nothing could be seen until two German destroyers suddenly

appeared out of the darkness. Norge’s

captain, Per Askim, gave orders to open fire at a range of about 800 yards. Due

to the difficult weather condition, it was hard to use the optical sights for

the guns, which resulted in the first salvo falling short of the target and the

others going over. The German destroyers returned fire and launched three

salvoes of two torpedoes each. The first two salvoes missed, but the last

struck Norge amidships, and she sank

in less than one minute, her propellers still turning. 90 of the crew were

rescued from the freezing water, but 101 perished in the battle which had

lasted less than 20 minutes.

Finland

Väinämöinen

Class (1931)

Other than

Thailand, Finland was the last country to build new coast defence ships. The

design of the Väinämöinen and the Ilmarinen was optimised for operations

in the Baltic archipelagos and their open sea performance was de-emphasized in

order to give the vessels shallow draft and super-compact design. On 3900 tons

these 300 ft. long, diesel-electric powered ships carried an armament of four

10” and eight 42 guns, plus lighter anti-aircraft weapons. Draught was just

under 15ft.

|

Väinämöinen in 1938

|

During the

“Winter War” of 1939-40 against the Soviet Union the ships’ freedom of action

was hampered by ice. Moored at the port of Turku, their anti-aircraft artillery

aided defence. During the “Continuation War” when Finland allied itself with

Germany after the latter’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, both

ships shelled Soviet land targets and cooperated with German surface forces to

lure out Soviet ships to battle. Ilmarinen

was sunk by a mine on September 13th and went down in just seven

minutes. From the crew of 403 on board only 132 survived. Thereafter the Väinämöinen saw little action and was

handed over to the Soviet Baltic Fleet in 1947 as a war reparation. The Soviets named

her Vyborg and kept her in service

for a further 6 years.

Thailand

Sri Ayudhya Class (1938)

The last

coast defence ships to be built, the Sri

Ayudhya and her sister Thonburi were

considerably smaller, at 2350 tons, than the Finnish ships. On this

displacement the 250 ft. long vessels managed to carry four 8” and four 3” guns,

plus anti-aircraft armament.

Thonburi and other Thai ships were engaged by Vichy French naval forces in the Battle of Ko Chang on January 17th 1941 and

suffered damage. She was beached to avoid sinking. Her sister did not arrive in

time to participate.

|

Drawing of Thonburi by

Dr. Dan Saranga

Downloaded with thanks

from http://www.the-blueprints.com/

|

Sri Ayudhya met

her end during a military coup in 1951 when a group of junior naval officers took

the Thai Prime Minister aboard at gunpoint. Though the ship attempted to escape from

Bangkok a critical opening-bridge was kept closed against her. Shelling from

land disabled her and she lay dead in the water in front of the Wichaiprasit

Fort, from where she was bombarded by artillery. AT-6 (Texan) training aircraft also bombed

her. Now burning, “Abandon Ship” was

ordered and the Prime Minister had to swim ashore along with the crew, but was

uninjured. The fires continued throughout the night and into the next day, leading

to the heavily damaged Sri Ayudhya

finally sinking on the night of July 1st 1951.

Sri Ayudhya’s loss

brought the 80-year era of the coast defence ship to an end.

.jpg)

+No.2.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)