This week's blog is very different in nature to the topics I usually write about. It reflects a very moving personal experience and I've drawn some lessons which are of relevance to us all. I hope you'll read it to the end.

.jpg) |

| A wall of names, thousands - wives, mothers, sisters, daughters, aunts ... |

I’m just back from a visit to Astana, capital of Kazakhstan.

It’s an amazing place – a new city dropped down into the middle of an empty

steppe - and is memorable for its large number of stunning modern buildings.

The discovery and development of vast hydrocarbon reserves have provided the

revenues for transformation of this former vassal-state of the old Soviet Union

and it is now a very self-consciously independent modern state. I had visited

previously and what made the greatest – and most moving – impression on me then

was not of the city itself but of the Alzhir women’s Gulag memorial about 30

kms outside. I returned on my latest visit and what follows here is an account

of what one finds there.

|

| Enemies - by family relationship - of the Soviet system |

Kazakhstan is a vast country, the ninth largest in the world

in terms of area, and much of it, including where Astana is located, consists

of thinly-populated steppe terrain, roughly comparable with prairies in the United States and Canada.

The Kazakh steppe is a harsh and difficult place to live – freezing in winter,

with temperatures below minus 30 deg C. for long periods, with howling winds

and driving snow, but hot and dusty in

summer.

.jpg) |

| More enemies of the Soviet system - some as old as three |

These climatic conditions made Kazakhstan an ideal location

for the Gulag labour camps of the Soviet era since the geography and climate were

efficient barriers to escape. In the Stalinist period, especially in the period of the purges from

1936/37 to the death of Stalin in 1953 there were large numbers of such camps,

not only for “political prisoners “ – many if not most of whom were convicted

on the grounds of suspicion of disloyalty –but for their family members, for

returned WW2 prisoners of war (capture by the enemy was regarded as a

punishable crime) and for large numbers of Poles deported after the joint Nazi-Soviet

invasion of 1939.

|

| The Alzhir memorial site - conical structure is the museum, dark strip behind is the wall of names |

The Alzhir memorial is established at a camp for female

relations of political prisoners and though the visitor is shocked at what they

see it is important to remember that this camp was only one of dozens of such

manmade hells in Kazakhstan. Alzhir was however the largest women’s camp in the

Soviet Union while it operated from 1937 to 1953 and thousands of women – and their

children – passed through it. These people were themselves accused of nothing

other than being the wives, mothers, sisters or daughters – even cousins – of people

who had been convicted of “betrayal of the Motherland.” The standard sentence was eight years but for

many climatic conditions alone could kill them in less than one. Even very young children were transported to

the camp – those under about the age of three staying with their mothers before

being taken to separate state orphanages. Pregnancy at time of arrest was no protection

and many babies were born in the camp.

Fear of “guilt by association” must have been the most

powerful single deterrent to internal opposition to Soviet rule. A man or woman

alone might be prepared to risk the consequences of punishment for themselves personally,

but most would hesitate when knowing that any action of theirs would draw the

full might of repression and imprisonment on other family members, direct and

indirect.

As one enters the site – beautiful with planted flower beds

when I visited last August, but much more bare now before the spring growth

kicks in – one is confronted with a preserved “Stalin Wagon”, the type of

railway box car used to transport the women in groups of up to 70 across the

vast distances of the Soviet Union, regardless of weather or season. Bare wooden shelving represented

accommodation and heating was by a single iron stove in the centre. Sanitary

provision consisted of buckets.

The approach to the museum is flanked by the ‘Arch of

Sorrow’, designed in the shape of a traditional Kazakh wedding head dress, and

beyond it memorial plaques for victims of from individual Soviet nationalities

and from Soviet-ruled countries in Eastern Europe. Two statues, one male, one

female, symbolise the two extremes of the Gulag experience. A man looks down,

broken in despair but a woman, stares into the future, seeing life beyond current suffering.

Beyond lies the circular museum building, and

behind it, most terrible of all, are black marble walls inscribed with the names

of thousands of prisoners, some of whom died there, some of whom survived.The tour of the museum starts with an emotionally-wrenching

video in which ex-prisoners, and their children, tell their stories. They came

from every background. Some regarded themselves as loyal Communist Party members

– the opening testimony is from the surviving sister of Marshal Mikhail

Tukhachevsky, the young military genius who had been so successful in the Russian

Civil War, and whom Stalin purged as a potential rival. She also lists relations

of other “Old Bolshevik” stalwarts. Most prisoners however were of humbler

backgrounds and since every citizen was subject to arbitrary arrest, were their

loyalty to Comrade Stalin to be suspect, age, occupation or political views –

or absence of them – were no protection. The saddest testimonies of all are

from surviving children who ended up either in state-run orphanages or were

looked after by relatives, and who, like their mothers, made desperate attempts

to remain in contact. They remembered the mother they had seen at time of

arrest and often failed to recognise the human wreck who, if she was lucky, survived

to be released after serving her sentence.

|

| Door to Interrogation Room |

The exhibition about life in the camp starts with a

sculpture set around the original door to an interrogation room. I found the photographs on display to be

poignant beyond belief – they show prisoners, a few only , but representing the

thousands who suffered there. Most show the women before their arrest – some

young, some old, some Russian, others from various Soviet nationalities, some

stunningly beautiful, others careworn, but each with her own personality, her

own family, her hopes and fears and ambitions, her own right to a decent life. They

could be your or my grandmother, mother,

wife, sister, daughter, cousin, aunt. When arrested many were told they were to

meet their arrested family members so they wore their best clothes to the

prison and some managed to bring a few personal belongings – a cruel joke to

mark their descent into hell.

The women came from all walks of life – famous actresses,

accomplished doctors and intellectuals, ordinary women from every part of the

Soviet Union. They were “rehabilitated”

after serving their five to eight-year

sentences and. Some never found their

way back to their families however - their relatives and children had died either

in the Gulag system or in the war and many of them built new lives for

themselves in Kazakhstan. The last

remaining Alzhir survivor still lives in Astana.

.jpg) |

| Barrack hut - adobe walls, sod roof, one stove, home for several women for eight years |

The camp was, and the memorial is, surrounded by a vast open

plain, much of it flooded at this time of year, April, after the snows have

melted. In 1937 the first prisoners

arrived at an open expanse and had to build their camp from scratch, working up

to their waists in water to curt reeds for binding the mud of the adobe bricks

used to construct their huts. One such barrack hut has been recreated and inside

it is a crude but emotionally powerful diorama showing a 3-year old child being

taken from its mother to be sent to an orphanage. The roof consisted of rafters

covered by grass sods and there was a single stove. The prisoners slept on

rough wooden bunks and during the day many of them worked making uniforms – so

much so that the camp received a commendation for its contribution to the Soviet

victory in 1945.

.jpg) |

| Sign at reconstructed barrack hut |

.jpg) |

| A child's letter to its mother |

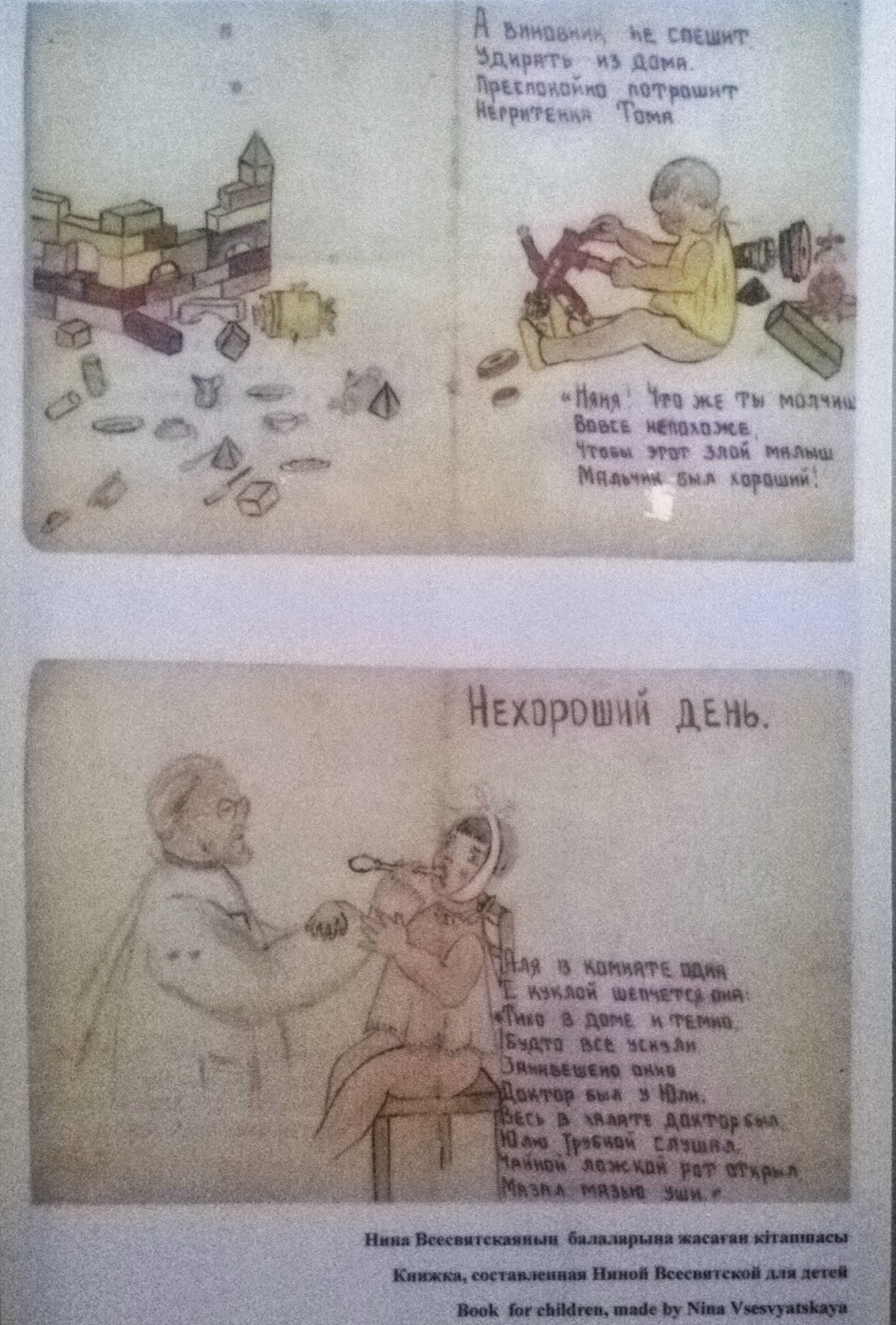

The most heart-breaking display showed letters that the

women received from their children and the small items they in turn made for

them from scraps and managed to get sent to them. It is impossible to see these

without choking with emotion – children’s letters and drawings reassuring their

mothers that they were thinking of them, working hard at school, looking

forward to their return. One prisoner made a little story book, illustrated by

herself.

Several factors helped to make the life of the women more

bearable. The commandant was, by most

accounts, if not a gentle man then not a sadist. The camp was located close to a Kazakh

village and the villagers did all they could to help the women – giving them

extra food to supplement their meagre camp rations. The first time this happened the women

thought the villagers were throwing stones at them – closer inspection showed

the ‘stones’ to be kurt – small hard balls of traditional dried cheese. Helping prisoners in this way was itself a

crime that could result in similar incarceration. Despite this however a combination of inadequate food and clothing, cold, despair and overwork killed large numbers.

.jpg) |

| A letter to a prisoner from her son and daughter |

.jpg) |

| A few names from thousands - each one valuable to so many loved ones |

The camp was closed after Stalin’s death. The memorial complex was opened in 2007 and as

a newly-independent nation Kazakhstan has worked hard to acknowledge what

happened on its soil in the name of the Soviet Union and to keep the memory

alive so that it cannot happen again. May

31st each year is dedicated to the memory of the victims of

political repression.

|

| This lady - first name Fatima - seems to have been a Kazakh. I hope she survived |

At the memorial I experienced the same emotions as when I

visited the yet more dreadful site of Auschwitz some years ago. I felt extreme

sadness, but also limitless reassurance that, no matter what oppression can be inflicted

by the forces of evil, all that is good and admirable in humanity will somehow

survive. I brought away with me three lessons that should never be forgotten;

·

Freedom is precious and is worth any sacrifice

to preserve it

·

There’s nothing more beautiful than a human life,

any human life

·

We don’t recognise the infinite value of our

happiness in normal times

.jpg) |

| A child's letter to her mother - no photograph, just her self-portrait |

|

| A book made for her children by a prisoner |

|

| The three walls of names - thousands of them - are unforgettable |

P.S.

Many thanks to the very knowledgeable and fluent-Russian speaking “Ersatz Expat”

of Astana who accompanied me on this visit to the Alzhir memorial. A link to

her own highly-entertaining blog can be found on my blog list in the column to the

right.

A bleak account, but one which needs telling. Such misery, such waste. 'Stalinist purges' are not just words, but the minutiae are brought home here.

ReplyDeletePainful reading, but thank you.

Thanks Alison - I felt I had to write it as soon as I could

DeleteAccording to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in "The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956", not only captured Russian army personnel, but also any Russians who served on foreign soil during WWII, even decorated soldiers, were sent to the Gulags because Stalin considered that they were contaminated by foreigners (and their ideals) and could not be allowed to live among Russian citizens. This book should be a must read for everyone.Thank you for your post.Did you go to Kazakhstan for research for a new Dawlish book?

ReplyDeleteThanks Denise - the Kazakhstan trip was to see family members. Astana is about as far from the sea (except the landlocked Caspian) than anywhere on Earth but I was indeed on the lookout for indications that Dawlish (or Zyndram) might have found himself there in the 1880s - Great Game and all that. It is very sad that so little of the Aral Sea remains - another consequence of Soviet domination. As regards how families coped wit teh Gulag a superb and haunting book is Orlando Figes' "The Whisperers" - well worth reading. http://www.amazon.co.uk/The-Whisperers.../dp/0713997028

DeleteThanks for this post. I've been to Kazakhstan and read books by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Still, the horror touches me every time.

ReplyDeleteAgree - at times one feels that one's been walking on one vast graveyard.

DeleteThis is an absolutely amazing piece. It is also very movingly and beautifully scribed. Have you seen the movie Burned by the Sun? The play received a standing ovation at the National Theatre. It is not about the gulags but about May Day in a Russian Village during the Stalin period. The film has subtitles. Thank you for posting this. Russia has gone through terrible times. Yes, the Russian people have suffered.

ReplyDeleteThanks for this. I was there today, and was looking for more information to attach to my photographs. I appreciate your insights and writing.

ReplyDelete