The name HMS Vanguard

is associated today with the Royal Navy’s last battleship, scrapped in 1960. An

earlier Vanguard was however to meet an

even more unpleasant fate, and arguably a wholly avoidable one.

|

| HMS Vanguard |

The HMS Vanguard

launched in 1870 was one of a class of four ironclads, her sisters being Audacious, Invincible and Iron Duke.

The concept of a sea-going ironclad capital ship was only ten years old. HMS Warrior, the first of the type, and which

was as revolutionary in her time as HMS Dreadnought

four decades later, had become the starting point for a new type of warship.

The Vanguard and her sisters

represented a second generation of such ships. Their most notable departure

from the Warrior configuration was

that although Warrior carried her many

guns in broadside mountings, as warships had done for centuries, the Vanguard’s armament of much heavier

weapons was concentrated in a two-storey armoured box amidships.

|

| HMS Warrior - obsolescent in 1875 but today restored to her former glory at Portsmouth |

Vanguard and her

sisters (see table) were rated as “second-class”, of moderate dimensions

that were well suited for deployment on foreign stations, most likely singly. Iron Duke was to serve as flagship of

the China Station for four years form 1871 and was one of the largest ships to

transit the Suez Canal up to that time. Her sailing rig made her particularly

suitable for operations in areas, such as the Pacific Ocean, where coaling

opportunities were limited. All four vessels of the class were described as “good

and steady seaboats but slow under sail”.

By 1875 Iron Duke

had returned to home waters and was assigned, with her three sisters, with the ironclads

Hector, Defence, Penelope and Achilles, and the by-then obsolescent Warrior, to the First Reserve Squadron. In late August the squadron was based at

Kingstown (now Dun Laoighaire) the large artificial harbour on the southern side

of Dublin Bay. On the morning of September 1st the Squadron left Kingstown

in line, the majority of the vessels headed for Queenstown (now Cobh) further south

on the Irish Coast. This enormous force, splendid with their black hulls and buff funnels and masts, must have been a magnificent sight as

they passed, one by one, through the narrow-gap between Kingstown’s two projecting

mile-long piers.

|

| HMS Vanguard at sea under sail and steam power |

Six miles out, off the Kish Bank lightship, the Achilles broke away to head for Liverpool

and the remaining ships turned south. The sea was moderate, but a fog came on,

its density increasing. The ships had been proceeding at some twelve knots, but

speed was reduced to half this as the fog persisted. By a half-hour after noon the lookouts on Vanguard could not see more than fifty

yards ahead, and the officers on her bridge could not see the bowsprit. It is unlikely that the situation was any

better on the other ships.

|

| Contemporary illustration - Vanguard sinking and Iron Duke's damaged bows (l) |

The Vanguard’s

watch suddenly reported a sail ahead, and the helm was put over to prevent

running it down. The Iron Duke was

then following close in the wake of the Vanguard,

whose action brought the two vessels closer, presenting Vanguard’s port broadside-on to Iron

Duke’s bow. Unaware of any change, and blinded by the fog, the Iron Duke ploughed on. Only at the last

moment did her commander, Captain Hickley, who was on the bridge, see Vanguard emerging from the mist. He

ordered reversing of his engines, but it was already too late. The Iron Duke’s ram struck the Vanguard below the armour-plates, on the

port side, abreast of the engine-room. The rent made was very large—amounting,

as the divers afterwards found, to four feet length —and the water poured into

the hold in torrents. It was immediately obvious that Vanguard was doomed for this was still an age when compartalisation

and damage-control of iron vessels were in their infancy.

|

| Boats from both ships rescuing Vanguard's crew |

There was nothing more to be done but to save lives. The Vanguard’s Captain Dawkins ordered

abandonment and officers and men behaved calmly. At the risk of his life one of

the mechanics returned to the engine-room to blow down the boilers, so

preventing an explosion,. The water rose quickly in the after-part, and rushed

into the engine and boiler rooms, eventually finding its way into the

provision-room flat, through imperfectly fastened “water-tight” doors – which

proved anything but. Discipline was superb, the crew standing on deck as if at

an inspection and not moving until ordered. Boats were lowered by both Vanguard and Iron Duke and in the process of transfer the only casualty of the

disaster was sustained – a finger crushed between a boat’s gunwale and a ships’

hull. The actual transfer to Iron Duke

of Vanguard’s entire crew was

achieved in twenty minutes and Captain Dawkins was the last man to leave her.

Vanguard heeled

gradually over until the whole of her enormous flank and bottom, down to her

keel, was above water. Then she sank gradually, righting herself as she went

down, stern first, the water being blown from hawse-holes in huge spouts by the

force of the air rushing up from below. She disappeared some ninety minutes

after the collision.

|

| The court-martial |

The inevitable court-martial was to prove remarkable for the

statement by the then First Lord of the Admiralty – the minister responsible

for the Navy – that “we ought to be

rather satisfied than otherwise with the occurrence”. Edward Reed, the designer of both ships, and by

1875 a Liberal Member of Parliament, stated that ironclads were in more danger

in times of peace than in times of war. In peacetime, he said, they were

residences for several hundred men, and many of the water-tight doors could not

be kept closed without inconvenience. In wartime however they were fortresses, and

the doors would be closed for safety. Even

more remarkably, close station-keeping in a fog was not considered as contributing

to the disaster. The Court commented negatively on the conduct of the Iron Duke’s officers and indirectly

blamed the admiral in command of the squadron. The Admiralty could find nothing

wrong in either case and visited their wrath on the unfortunate lieutenant on

deck at the time.

Vanguard still

lies, largely intact, in some 150 feet of water off Ireland’s Wicklow coast.

She is reachable by experienced air-divers – and reaching her must be a magnificent

experience.

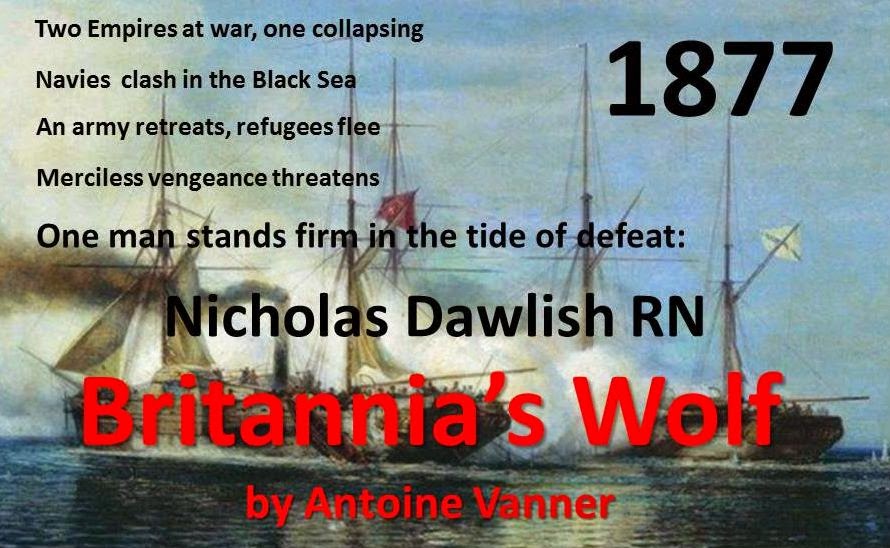

If you want to read about adventure in the age of transition from sail to steam, then try The Dawlish Chronicles, which so far stretch to five volumes. Start the adventure with "Britannia's Wolf" which features ironclads in combat, desperate land action in the depths of a savage winter, and murderous political intrigue. You can get it in Kindle or paperback format. Click on the image below for details.

Download a free copy of Britannia’s Eventide

To thank subscribers to the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list, a free, downloadable, copy of a new short story, Britannia's Eventide has been sent to them as an e-mail attachment.

No comments:

Post a Comment