|

| The Daewongun, 1869 |

A recent blog, “The

French Navy in Korea, 1866”, described Korean attempts in the 1860s to

retain its status as “The Hermit Kingdom”, cut off from contacts with the world

outside. The key figure in this was the sinister Yi Ha-ung (1821-1898), the “Daewongun” – a title meaning “Prince of

the Great Court” –who was to be a near-dominant player in internal Korean

politics for four decades until the late 1890s. Adept in playing off internal

and external forces against each other, his main objective was to limit

external contacts and to maintain traditional structures and culture unchanged.

This policy had led to large-scale and savage persecution of Christian converts

and French missionaries and these in turn were to lead to a brief French

punitive mission in 1866, as described in the previous blog. (Click here to read this).

|

| Korea, the "Hermit Kingdom", in the 1860s - exotic and isolated |

By the 1860s Western nations were already heavily engaged in trade with China, and since 1854 with Japan, which had been “opened up” to foreign merchants from 1854 and was now rapidly modernising. In Korea, however, the Daewongun, and the conservative interests allied to him, were not convinced of the merits of such contacts and were determined to preserve Korea’s isolation. It is against this background that in August 1866 an American owned vessel, the sidewheel-steamer SS General Sherman, was involved in an attempt to open trade.

The timing was ill-chosen to say the least, for feeling

against outsiders had been whipped up by the Daewongun and French intervention to avenge the slaughter of

missionaries and converts was imminent. Despite her American registration, the General Sherman’s mission was funded by

a British commercial company, Meadows & Co., which operated in China and

hoped to negotiate trading rights. Only the vessel’s Captain Page and Chief

Mate Wilson were Americans and there were two British citizens on board, the

owner, W. B. Preston, and a Welsh missionary, Robert Jerman Thomas, who had

been brought along as a translator. The crew consisted of thirteen Chinese and

three Malay seamen. Though loaded with a cargo of trade goods – cotton, tin,

and glass – the General Sherman also

carried two 12-inch cannon. The presence of these weapons which was to make the

vessel’s mission doubly unwelcome in Korean eyes.

|

| A view of the Korean coast |

In mid-August 1866 the General

Sherman sailed up the Taedong River on Korea's west coast towards

Pyongyang. Initial contact with Korean

officials were peaceful, if not

cordial – permission to trade was refused – and the ship proceeded unhindered

until it ran aground at Yangjak island,

close to Pyongyang. Korean attitudes were now hardening and on August 27th,

when an official boarded the vessel, Captain Page detained him, probably as a

hostage. This worsened the situation and an order arrived from Daewongun that if the prisoner was not

released, and if the General Sherman

did not leave at once, all on board should be killed. Departure was not an

option however – the level in the river had fallen – the ship had only reached

so far upriver due to heavy rains earlier and it was now firmly lodged on a

sandbank.

|

| A North Korean stamp commemorating the destruction of the SS General Sherman |

The details of what now followed are uncertain as nobody on

the General Sherman was to survive.

Hostilities erupted on August 31st and cannon were apparently fired

from the ship at Korean troops on the river bank. The confrontation lasted four

days and was brought to a head by fire-ships being drifted downriver towards

the immobile ship. Two attempts failed but the third succeeded in setting the General Sherman ablaze. Chinese and Malay

crew-members either died in the flames, or drowned when they jumped overboard

or were beaten to death when they reached the shore. The captain, mate, owner and

translator appear to have been murdered after capture. The Korean official they

had so unwisely taken hostage survived.

|

| A North Korean depiction of the destruction of the SS General Sherman It's not clear which of the figures is Kim Il Sung's great-grandfather! |

A century later this incident was to attain near-mythic

status under the later Communist Government of North Korea. The dictator Kim Il

Sung claimed that his great-grandfather was involved as an early opponent of US

imperialism. Like so much emanating from North Korea, the claim deserves to be

viewed with some skepticism!

|

| The steam-frigate USS Colorado |

The American response was tardy in the extreme. In early

1867 an attempt by a US warship to determine what had happened seems to have got

nowhere due to “foul weather” and a year later contact with the Koreans by the

USS Shenandoah confirmed that all who

had been on board the General Sherman were dead. Decisive action only came in May 1871 when the

US American Minister to China, Frederick

Low,was tasked with gaining an apology. He came in force, backed up by five warships

commanded Rear-Admiral John Rodgers who flew his flag in the steam frigate USS Colorado.

|

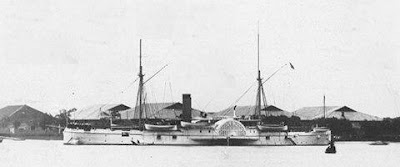

| The long-lived USS Monocacy - seen here at Shanghai in 1898 |

The American flotilla was a

powerful one – besides the Colorado

there were two sloops, Alaska and Benicia, as well as the paddle-gunboat Monocacy, and the screw-gunboat Palos. Between them they mounted 85

guns. The focus was on the Han River, on which the royal capital Seoul lay some

40 miles from the sea – the same approach taken by the French five years

earlier. The warships moored at the river mouth and gunboat USS Palos was sent to assess the possibility

of reaching Seoul. This vessel was fired

on by Korean forts defending the Han and it retired with two men wounded. When the Palos

was again fired upon, on June 1st, the paddle-gunboat Monocacy silenced the battery

responsible. Further negotiation attempts failed in the nine days that followed

and Minister Lowe and Rear-Admiral Rodgers finally authorised punitive action. This

was to involve the capture of Korean defences on Ganghwa Island – a total of

six forts and four coastal batteries.

|

| Officers of the USS Colorado |

The landing

went ahead on Jun 10th, preceded by a bombardment by the warships.

The force sent ashore consisted of 542 seamen and 109 marines, together with and

six 12-pounder howitzers. The first fort to be attacked fell without

significant resistance and the American force pressed on to the next, which was

now labelled “Fort Monocacy”. This in turn was to fall and the landing forces spent

the night in it – the first US forces to be stationed on Korean soil.

|

| Hand-to-hand fighting in one of the Korean forts |

The

attack resumed the following day, the force offshore bombarding the forts while

the landing party attacked from the land side as the barrage ended. The key to the

Korean defence was a position labelled by the Americans as “Fort McKee” in

honour of the lieutenant, Hugh McKee, who led the assault on it. Resistance by

some 300 Koreans armed with antiquated matchlocks and swords was fierce but

lasted only fifteen minutes – the fact that the Americans were armed with

Remington rolling-block carbines proving a significant advantage. McKee, who was the

first to enter the fort, was fatally wounded but Commander Winfield Scott

Schley – who was to win renown in the victory over the Spanish fleet at

Santiago in 1898 – was close on his heels and he shot the Korean who had killed

him.

|

| Korean prisoners on the Colorado |

|

| Captured "Sujagi" - Corporal Brown in middle |

By the end of

the day the island and its defences were in American hands. Korean casualties amounted

to 243 dead, a small number of wounded and twenty prisoners. The Americans suffered

three dead and ten wounded. Nine sailors and six marines were later awarded the

Medal of Honor, among them a marine corporal, Charles Brown, who captured a

large Korean standard or “sujagi”. These

were the first Medals of Honor to be won on foreign service.

Then, after the

victory – nothing. The Koreans still refused to negotiate and there was nothing

the Americans could do about it. The first external treaty to be negotiated was

with Japan, and not with a Western nation. It was not until 1882 that the United

States finally signed a treaty with the Koreans,

at a time when the Daewongun was

temporarily side-lined by his equally clever and ruthless daughter-in-law,

Queen Min. (This provides the background to my novel Britannia’s Spartan).

Recently published: Britannia’s Spartan

This latest novel in the Dawlish Chronicles series is set in Korea in 1882 and a sinister role is played in it by the Daewongun.

This latest novel in the Dawlish Chronicles series is set in Korea in 1882 and a sinister role is played in it by the Daewongun.

Click below for more details for both paperback and Kindle versions:

No comments:

Post a Comment