It is always gratifying to an author to received feedback from

readers, particularly when detailed research to support a story is recognised

and appreciated. I was therefore delighted to be contacted recently by an

American reader, Douglas R. Smith, who was intrigued by the central role played

in my novel Britannia’s Spartan by

HMS Leonidas, a fictional member of the

innovative and real-life Leander

class of “protected cruiser” which entered service with the Royal Navy in the

1880s. I’m proud therefore to welcome Douglas as a guest blogger today. I’ve no

doubt you’ll enjoy his article.

PROTECTED CRUISERS IN

THE PRE-DREADNOUGHT ERA

by Douglas R.

Smith

The British Empire was vast and overextended in the late

1800s, and dependent upon vulnerable sea lanes. To compensate it had a Navy

equal to the next two contenders combined. British bankers and businessmen

built a network of intercontinental telegraph lines, reaching all of the way to

New Zealand by 1876, with London at the center. The role of protected cruisers

was for protecting commerce, and raiding that of the enemy, often operating

distantly and independently around the globe.

"Britainia's

Spartan" by Antoine Vanner is the story of the shakedown cruise of the fictional HMS Leonidas, first of her class. Captain Nicholas Dawlish has earned the honor of being her first commander. We have followed

his meteoric career in earlier books, and like all career people, he must struggle to find a

balance, and determine if that balance is worth the personal cost. In a similar

way a warship must find a balance between speed, firepower, and protection, and

do so at an acceptable cost in lives and resources. This is an outline of naval

dynamics with respect to protected cruisers in the dawn of the Pre-Dreadnought

Era, when hydraulics, electricity, and triple reciprocating steam engines were

enhancing the capabilities of warships, but before submarines, destroyers, and

airplanes, much less carriers and tenders for them, changed the nature of naval

warfare.

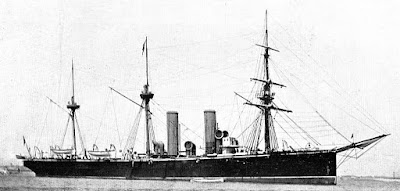

|

| HMS Leonidas - Nicholas Dawlish's command in Britannia's Spartan |

Armored cruisers (

the Russian Navy favored them ) relied on a steel belt for protection, much the

same as the battleships. Often a belt included a ram in the bow, a relic of

ironclad steamships fighting against wooden ships. But since weight was the enemy of speed,

armored cruisers were little better than battleships at commerce raiding. Not

too cost effective. Protected cruisers relied on clever use of curved steel to

deflect shells away from, and coal bunkers to protect, the machinery and

magazines below water level. It worked well provided you didn't collide with

armored ships. The weight savings resulted in greater speed and the range to

defend a far-flung empire.

It's always nice to

have superior range in a main weapon. That's been true ever since the

trebuchet. You can hit the enemy, but they can't hit back. HMS Leonidas had a main battery of all

6" breech loading rifles. A bigger gun could do more damage, but a

contemporary 7", 8", 9",

or even 10" breach loader wouldn't necessarily have more velocity,

accuracy, or effective range ( about 10,000 yards). It would require separate

powder charges and shells in the magazine, complicate handling, adding weight and reducing speed,

particularly as a bow chaser, where it would be most advantageous. The

alternative solution would have been to develop lighter shells for long range

situations, but the trade-off would be reduced impact.

Japanese

protected cruiser Izumi left

elevation plan

The British-built

protected cruiser Chilean Esmeralda

1884 (aka IJN Izumi after 1894 ).

A bow ram,

10" chasers, a 6" broadside, and 3 sizes of other guns,

but no

torpedo launchers until the sale and refit.

Source: Janes Fighting Ships, 1904

edition Sampson, Low, Marston and Co, London

|

In Nelson's era, sailing ships of the line tended to have

lighter weapons as the decks got higher, ranging from 32-pounders to swivel

guns. It didn't much matter at "pistol shot range" in the days of

sail when rate of fire was the key. As

the range opened up in the Pre-Dreadnought Era, it became difficult to correct

the aim because they couldn't differentiate the splashes. The continuous smoke

from the rapid-fire weapons never cleared, so they couldn't see well enough to

aim anything properly. The innovative “all big gun” design of the HMS Dreadnought solved these issues.

Adding extra "tools" to the armament to anticipate

a multitude of situations, such as several small rapid-fire breach loaders of

various sizes to defend against torpedo boats, is a design temptation for an

independent command. This "Swiss Army knife approach" requires more

crew and training, complicates ammunition storage and handling, and versatility

comes at the expense of role specialization and refinement.

Torpedoes as we know

them were in the early stages, with an effective range limit of only 800 yards,

less for a moving target. Lethal, but more of a coup d' grace than a stand-off

weapon. HMS Leonidas carried two launchers on each broadside. Pairs of

torpedoes are much harder to avoid than solo ones, but crippled ships aren't so

nimble. Perhaps it wasn't a very practical addition to the armament.

An alternative

arrangement would be for the cruiser to carry a pair of torpedo boats, (like

HMS Leander, and the fictional Kiroshima in Britannia’s Spartan) which could be launched for coordinated night

attacks. More skill, but more effect. In terms of costs in cash and lives, it

takes a lot of torpedo boats to equal a battleship, so they were the emerging

threat at the time. France embraced them as part of her “Jeune Ecole” doctrine. The

Americans were developing flywheel powered torpedoes, which had no telltale

bubble trails. A pair of torpedo boats carried aft would lift the bow and

improve the ship's trim, offer an option against a battleship (when a gun fight

was out of the question) , and would enhance blockading a hostile port or

protecting a friendly one (more so with the addition of a few sea mines) . They

might also come in handy for patrolling, carrying messages, search and rescue,

or on convoy duty. They add weight, but would replace some boats and torpedo

launchers.

|

| Gatling being fired from a fighting top |

Ships retained masts, yards, and sails as backup propulsion

and to stretch the coal supply on long voyages, but the sailing rigs had less

area and the ships more weight than their predecessors, and weren't practical.

In combat, these rigs often became a liability that would obstruct a battery,

create splinters, or act as a sea anchor when hit. Radios hadn't been invented

yet, so they didn't need an antennae mast. They did still need signal halyard

and lookout platforms, and they were good places to mount Gatling guns and

search lights to defend against night torpedo boat attacks. An observer or

gunner couldn't see much from a mainmast close to the smoke stacks. A foremast

and it's supports interfered with the bow chaser and the view from the bridge.

It took years for naval architects to sort things out.

The first designated torpedo boat destroyer went into

service in 1895. Navies would adopt submarines at the turn of the century,

radio 1905, HMS Dreadnought in 1906,

and floatplanes circa 1910. In 1912 the effective range of the torpedo was as

much as 6,000 yards. By then the value and versatility of the destroyer was

proven, and they were replacing torpedo boats. Naval warfare would become

"modern". But in the early 1880s, other cruisers, battleships, and

torpedo boats were the recognized perils, and how to optimize the new cruisers

to fulfil the role of commerce raiders or protectors was the question.

Douglas R. Smith was born in Pennsylvania in 1959, where he

developed an interest in history and reading historical fiction. This included

Pre-Dreadnought navies, because they established both Japan and the USA as

world powers. He worked in agriculture, sales, and insurance. Now he and his

wife Karen are in Wisconsin, enjoying their retirement, dining, Disney, and

travel.

Britannia's Spartan

Six-inch breech loading guns represented the cutting edge of naval technology in the early 1880s. In my novel Britannia’s Spartan they are seen in use on both British and Japanese ships. The splendid woodcut below shows Japanese crews managing just such a weapon in the war of 1895 against China.

Download a free copy of Britannia’s Eventide

To thank subscribers to the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list, a free, downloadable, copy of a new short story, Britannia's Eventide has been sent to them as an e-mail attachment.

No comments:

Post a Comment