One tends to think of “marooning” – abandoning a seaman alone on an uninhabited island – as being a punishment associated with buccaneers and pirates in the late 17th and early 18th Centuries. It is therefore somewhat of a shock that what was probably the last instance of such retribution occurred in the Royal Navy as late as 1807. The story is a fascinating one and it underlines just how omnipotent and capricious a captain could be in the days before radio once his ship had disappeared over the horizon.

|

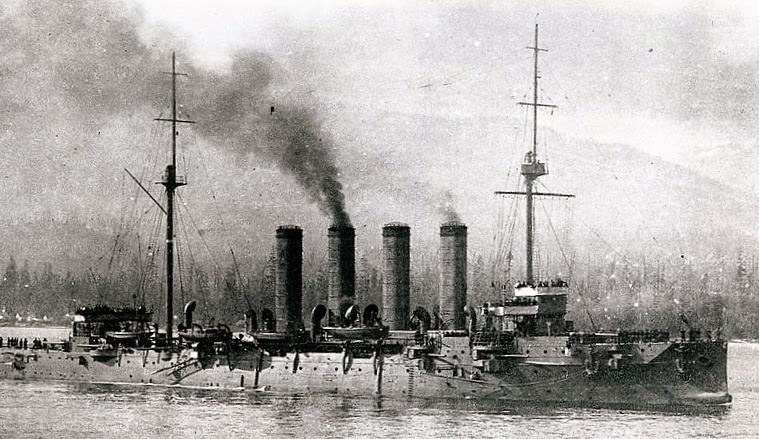

| The Cruizer class brig HMS Alacrity engaging the French Abeille in 1811 HMS Recruit would have looked very similar |

|

| Shipboard Carronade 1808 |

HMS Recruit was a 100-ft long brig-sloop of the Cruizer class, of which 110 examples were built for the Royal Navy between 1797 and 1815. Small as they were, they carried a very heavy armament – two 6-pounder bow chasers and no less than sixteen 32-pounder carronades. At short ranges the carronades gave the Cruizers a nominal broadside weight greater than that of a 36-gun 18-pounder frigate. The advantage of the design was that the two-masted rig and the use of carronades, with their small gun crews, allowed this to be achieved with a crew one third the size of a frigate's. These vessels were to see very active service.

The Cruizer design was already a proven one when the newly commissioned Recruit headed for the West Indies in July 1807. Her captain was the 24-year old Commander Warwick Lake, later to be 3rd Viscount Lake (1783–1848). In view of what was to follow one wonders if he was not influenced by the example of his grandfather, General Gerard Lake, 1st Viscount Lake (1744 – 1808) whose suppression of rebellion in Ireland in 1798 was to be marked by extreme brutality. This reached a climax in the defeat of the rebel army at Vinegar Hill, County Wexford, and brought him into conflict with the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord Cornwallis (of Yorktown fame) who instituted an amnesty to encourage rebels to lay down their arms.

On taking the Recruit to sea Lake encountered a problem common to most captains of his time – shortage of men. He solved the problem by putting in at the Cornish harbour of Falmouth and boarding the privateer Lord Nelson, despite her being under protection of latters of marque. Several men and boys of the privateer’s crew were pressed, among them a blacksmith called Robert Jeffrey, whose trade made him especially valuable at sea.

Lake, according to one account “profligate and reckless”, now headed for the West Indies and by November was cruising in the Caribbean. Water was in short supply, and according to Lake’s later account Jeffrey stole some rum in a bottle from the gunner’s cabin. It’s not obvious that this offence was followed up but Jeffrey was to admit that on December 10th he drew off two quarts of beer from a cask intended for the captain’s personal use. A shipmate informed on him and Jeffrey was placed on a “black list”.

|

| "Do you see that rock?" Victorian depiction of Lake emerging drunk on deck The uniforms look too pristine for realism! |

Three days later the Recruit was passing the island of uninhabited island of Sombrero, the northernmost island of the Lesser Antilles. It is tiny - little over a mile long and a quarter wide and only 94 acres in area – and is devoid of water. Commander Lake came on deck after dinner – apparently under the influence of drink – and decided that he now had an opportunity to punish Jeffrey. He is reported to have said “Lieutenant Mould! Do you see that rock? Lower the boat instantly. I’ll have no thieves on board my ship! Man a boat and set the rascal on shore!”

|

| The waterless Sombrero Island - also known as "Hat Island", little over a mile long |

Jeffrey was now taken to the island in the clothes he stood up in, but without shoes, food or water. Seeing that his feet were being cut by the rock Lieutenant Mould gave him a pair of shoes ,together with a knife and a handkerchief donated by a midshipman. Mould seems to have delayed, in the hope that Lake would change his mind but in the end had to return to the ship, leaving Jeffrey stranded.

|

| Jeffrey, immaculately uniformed, marooned - another Victorian illustration |

The Recruit now headed for Barbados to join the squadron there under Admiral Sir Thomas Cochrane. The story of the marooning began to leak out, causing general outrage, and Lake was ordered to explain himself. Cochrane, enraged, reprimanded Lake for brutality and ordered him back to Sombrero with the Recruit to find Jeffrey. On landing, no sign of him was found other than a pair of trousers – apparently not Jeffrey’s – and a tomahawk (a common boarding weapon). When the Recruit returned empty-handed the Admiral assumed that Jeffrey had been picked up by a passing ship.

Anger was widespread when the story reached Britain and Lake was court-martialled on board HMS Gladiator in Portsmouth in February 1810. Despite an attempt to pass some of the blame to his lieutenants the court found him guilty and dismissed him from the navy.

Jeffrey’s whereabouts were now the subject of impassioned interest, questions being asked in the House of Commons and the Government kept under pressure on the case. It finally emerged that he was in the Beverley and Marblehead area in Massachusetts and a ship was sent to bring him back, arriving in Portsmouth shortly after Lake’s court martial. Jeffrey had survived nine days on the rock, in extreme privation, before a passing ship, the American Adams, had spotted him. He had been unable to kill any of the abundant sea birds (the rock was later mined for guano) and he had been saved from death by thirst by a rain shower, having sucked up water from crevices through a quill.

Jeffrey – who had been unlawfully pressed in the first place, was discharged from the navy, was given his arrears of pay and was taken to his home at Polperro by a naval officer. The entire community turned out to welcome him and an eyewitness reported that “the meeting between the mother and her son was extremely affecting and impassioned.” He accepted a payment of from Lake of £600 – a fortune in those days, when a domestic servant might earn £10 per year – on condition that he would not press legal action against him. He told his story in London theatres and thereafter bought a coasting schooner. He did not however prosper and he died young of consumption, leaving a wife and daughter in poverty.

|

| HMS Recruit's moment of glory - crippling the Hautpoult 17th April 1809 |

The Recruit was subsequently to have a very active career. Her new captain was Charles Napier (of later fame ) who engaged the French corvette Diligent in 1808, driving her off only after a lucky shot ignited an ammunition store but suffering some 25% casualties in the process. The following year, 1809, saw the Recruit, after repairs, involved in the capture of Martinique, Napier himself landing with a small party, capturing a French fort, turning the guns on their previous owners and playing a key role in the final victory.

A French squadron of three 74-gun ships and two frigates had been end route to relieve Martinique but now turned back, chased by a British force that included a captured ex-French 74 HMS Pompée as well as Recruit. For three nights and two days the Recruit managed to hang on the tail of the French squadron. On 17 April 1809 she managed to bring the Téméraire class 74-gun Hautpoult under fire – and it was now that the carronades were used to deadly effect. The Hautpoult's mizzen mast was brought down, slowing her so that HMS Pompée could engage. The Hautpoult was captured after sustaining very heavy casualties in a 75 minute action. Taken as a prize, she was renamed Abercrombie, and was briefly given to Charles Napier of the Recruit. More valuable still to Napier was that he achieved the dream of every sea officer of his time – being made “post”, so that his rank of captain was made permanent.

The Recruit’s subsequent service was in North American waters in the War of 1812 – including being trapped in ice off Cape Breton in 1813, with more than half her crew suffering from scurvy as supplies of fresh produce ran out. Thereafter she was to be active on the American East Coast, capturing several privateers and merchantmen.

HMS Recruit was paid off when peace returned in 1815 and she was sold in 1822. For a small vessel her record of active service was dramatic in the extreme, showing, once again, that the reality of warfare in the Age of Sail was every bit as spectacular as it is depicted in historical naval fiction.

|

| The Recruit's unlucky Cruizer-class sister HMS Frolic being captured by USS Wasp 18 October 1812 |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)