Two recent blogs described the loss of low-freeboard

monitors in the open sea, the Dutch Adder

in 1882 and the Russian Rusalka in

1893. In both cases the inadvisability of taking vessels designed for protected

coastal waters into open-sea conditions was a major contributory factor to the

disasters.

|

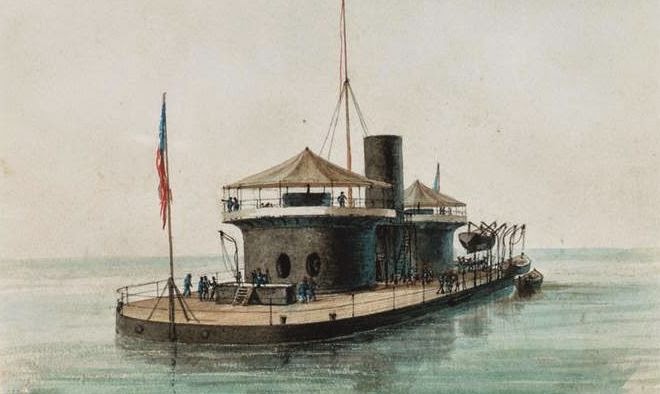

| USS Miantonomoh by Francois G. Roux (1811-82) |

A much earlier monitor did however make a very spectacular

ocean passage in 1866/7. This was the twin-turret USS Miantonomoh, the lead ship of a class of four wooden-hulled but

ironclad vessels authorised in 1862, soon after the original USS Monitor had made her spectacular debut.

Details are provided in the table.

Commissioned in late 1865, too late to play a role in the

Civil War, the Miantonomoh was

selected to make an extended cruise to European waters. The most important objective

was to maintain good relations with Russia, which had proved itself supportive

of the Union cause during the war, and had demonstrated this by a squadron

visiting New York at the height of the conflict. Purchase of Alaska by the United States was

now also on the cards and there was every reason to ensure a cordial atmosphere

for negotiation. The ostensible reason for the trip was to present Czar Alexander

II with a copy of a Joint Resolution of

Congress which congratulated him on his survival of a recent assassination

attempt (probably all the more heartfelt in view of President Lincoln’s death in

a similar incident the previous year). The responsibility for this diplomatic

task was assigned to the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Gustavus Fox, who was

also instructed to gather information of European naval strengths. Pride in

showing off American technological progress, and in the nation’s emergence as a

major power after the Civil War, probably also played a role.

.jpg) |

| USS Miantonomoh as completed |

.jpg) |

| USS Augusta - seasoned veteran of Union blockade dury |

.jpg) |

| The long-serving (1863-1903) USS Monocacy, sister of USS Ashuelot |

The small flotilla touched in briefly at St. John’s, Newfoundland. Here, a witness quoted in a Victorian-era

book, and who appears to have been a Royal Navy officer, was stubbornly determined

not to be impressed:

“Notwithstanding a

certain eagerness to behold a specimen of their floating batteries, curiosity

was not destined to be gratified until nearly two years after the close of the

American War, when the United States Government determined on sending a

representative—the Miantonoma (sic)—to

make a tour of the world. The object of this resolution was to prove that the American

invention was not a mere floating battery, but was destined to revolutionise the

system of armour-plated ships. The Miantonoma was accompanied when she made her appearance in the harbour of St.

John’s, Newfoundland, by two tenders … The Miantonoma was a twin-turreted monitor, carrying two of Parrot’s 480 pounder

smooth-bore. Her spar-deck, which was flush fore and aft, was about two and a

half to three feet above the surface of the water in harbour. What we would

call the gun-deck was below the water-line some eight feet, and here at sea

during any sort of rough weather, the men were compelled to live. Air was

supplied (faugh! what an atmosphere it was, even in harbour!) by means of pipes

which ran up to a scaffolding—I can find no better name for the structure—elevated

above the spardeck by fifteen feet. Here were the wheel-house and a place for

the look-out. But as it was apprehended that the first respectable gale would

take charge of the flimsy structure and sweep it all away, a ‘preventer’

steering apparatus worked below, and knowledge was gained of what was going on

in the upper world by means of reflectors. Two things struck the eye of an

observant stranger on gaining the side. The first was the formidable appearance

of the turrets—the latter, mirabile dictu, the number of spittoons!”

|

| Contemporary illustration: USS Miantonomoh passing a Royal Navy Ironclad, possibly at Portsmouth |

|

| Russian Monitor Veschun of the Uragan class |

The Miantonomoh left

Britain in mid-July, en route to the Russian capital. She stopped off at

Copenhagen – where she was inspected by King Christian IX and the royal family –

and then steamed on to be met near Helsingfors (now Helsinki) by eleven ships

of the Russian Navy, including four monitors of the Uragan class (built as copies of the US Navy’s Passaic class), and escorted to the main Russian base of Kronstadt,

just outside St. Petersburg. Here she was to be the centre of attention form the

czar himself as well as leading Russian naval officers. She stayed a month and

her commander, Captain Alexander Murray, was later to write: "We were the victims of a hospitality

which I did not believe had an existence out of America, and...of a generosity

which does not often fall to the lot of navy officers anywhere;...."

The triumphant progress continues, from Russia to Stockholm,

the Swedish capital, in mid-September and then on to Kiel in Northern Germany, and

then on to Hamburg, where she was apparently inundated with admiring visitors. The

Miantonomoh then sailed south, visiting

French, Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian ports during the next six months,

showing the flag where it might never have been shown before. She finally left European

waters, from Gibraltar, in mid-May 1867 and reached Philadelphia two months

later via the Canary and Cape Verde Islands and the Bahamas. Once again she

appears to have been towed, and presumably battened down, over these ocean stretches. The total cruise

was of some 17,700 miles. Except for a

short commission in 1869 she was to see little more service.

|

| The "Repaired" USS Miantonomoh - she was to serve in the Spanish-American War |

Wooden-hulled, despite her armour-cladding, the Miantonomoh’s days were numbered. In 1874, by a legal fiction that avoided

allocation of funds for new naval construction, funds were allocated by Congress

for "completing the repairs" of the Miantonomoh and three other monitors. The "repairs"

consisted of the constructing of new vessels under the guise of repairing the

old ones. She was broken up in 1875 and but few of her materials were used in

the building of the larger, more heavily armoured, iron-hulled “New Navy”

monitor which became the second Miantonomoh.

But her career is another story.

.jpeg)

_off_Spithead_1836.jpg)