When thinking about war at sea in the Age of Fighting Sail one’s

attention is immediately drawn to the ferocity of battle when ships engaged at

close quarters. In actuality however combat was relatively rare but wreckage in

stormy weather remained a constant – and exhausting – hazard at all times. One

is indeed struck by the number of ships – and lives – that were lost without

any intervention by the enemy. The Royal Navy was more vulnerable than those of

other maritime powers since British strategy rested on keeping at sea – and

dominating it – whether on close blockade of hostile coasts or bases, or cruising

to destroy enemy commerce, or projecting force anywhere in the world, from the Caribbean

to Java, from Egypt to Argentina.

|

| The nightmare of shipwreck on a lee shore - painting by Francis Danby (1793-1861) |

Keeping at sea did however mean inevitable

exposure to extreme weather, in many cases with fatal consequences. For all the

professional seamanship of ship’s officers and crews, sailing ships were, by their

very nature vulnerable, and never more so than when forced towards a lee-shore.

One example – a terrible one – of such a loss was that of HMS Sceptre in 1799.

|

| A third-rate, in this case HMS Bellerophon - Sceptre would have looked generally similar |

The Sceptre was a

62-gun third-rate ship of the line which had entered service in 1782, in time

to participate in the Battles of Trincomalee and of Culladore, off the Indian coast,

the last significant engagements of the Anglo-French was that had grown out of the

American War of Independence. She was laid up until 1794 and on recommissioning

participated in actions off Haiti and St. Helena. She spent a long time

thereafter at Cape Town – captured from the Dutch in 1795 – and was described

to have become “weak and leaky” there. Notwithstanding this she was to return

to Indian waters in early 1799, escorting a convoy and carrying an entire army

regiment – the 84th – herself. She leaked so badly in during one spell of bad

weather that she survived only by pumping. On reaching Bombay she was docked

and was strengthened by large timbers, known as riders, which were bolted

diagonally to her sides fore and aft. That this should have been necessary for

a relatively new ship indicated that the structure was in very poor condition. Now

repaired, she set out on her return voyage, reaching Cape Town in late October.

On November 5th, while moored in Table Bay, Cape

Town, a strong wind began to blow from the North West – a direction against which

the bay offered no shelter. No danger was anticipated however and flags were

flown, and a salute fired at noon, to celebrate “Guy Fawkes Day”, commemorating

the frustration of the Gunpowder Plot in 1605. By early afternoon however the wind

was at gale force and the captain ordered top-masts to be struck (i.e. taken

down) and the fore and main yards lowered to reduce drag. Soon afterwards a mooring cable parted but another

anchor was dropped, with two guns attached to increase its holding power. By

early evening even this was proving insufficient to hold the ship and a boat

was launched to cross to HMS Jupiter,

a fourth-rate moored close by, to secure a cable to her. The waves were so

violent however that the boat capsized and its crew drowned. The Sceptre was now helpless in a raging

sea. No help could reach her from the land and officers who had gone ashore the

previous evening could only watch helplessly.

At eight in the evening a new horror manifested itself, a

fire below decks, its origin unclear. Dense smoke was rolling from the hatches

in such volumes that it was impossible to go below to fight it. Two hours later

the helpless ship drove on to a reef, broadside towards the shore and heeling

to port towards the sea. The captain ordered the main and mizzen masts to be

cut away and this was done – discipline seems to have been well maintained even

at this desperate juncture. Lightened by the masts’ fall, the ship lightened and

rose free from the reef, moving closer to the shore and giving hope that she

might be thrown high enough upon the beach for all to be saved.

|

| Loss of HMS 'Victory, 4 October 1744' by Peter Monamy (1681 - 1749) (Not Nelson's Victory, but an earlier ship. The Sceptre, in distress, might have looked like this) |

|

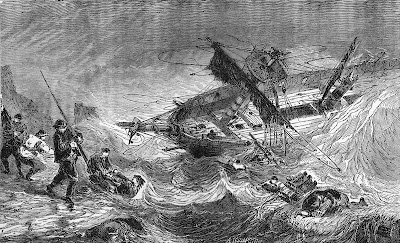

| HMS Sceptre's destruction as imagined in a 19th Century illustration |

The tragedy was played out close the shore, so that the crowds

that gathered there – townspeople, soldiers from the garrison – saw the horror unfold

but found themselves powerless to help. Fires were lit to guide swimmers but

many of them were killed by the churning wreckage as well as by drowning. Only

a handful reached the shore alive and the next morning three waggon-loads of

dead bodies were gathered for burial. The death toll, which included the captain,

was horrific – 349 seamen and marines were killed or drowned. Of the 51 who

reached the shore nine were so badly injured as to die there.

One of the survivors of the disaster was “The Indestructible

Admiral Nesbit Willoughby”, whose story has been told in an earlier blog (clickhere for details). Then a lieutenant, he was lucky enough to be one of the Sceptre’s officers who were ashore and who

were forced to watch from the beach. Thirteen years later this extraordinary

man was to survive the horrors of the retreat from Moscow as a prisoner of the French.

One cannot wonder whether he was lucky, by surviving these and other adventures,

or unlucky in being an apparent magnet for danger!

Britannia’s Shark by Antoine Vanner

Historic naval

fiction moves on into the age of Fighting Steam. Click here for more details ofthis story of the birth of a new weapon, of savage repression and revolt by land, of survival at sea, and below it.

No comments:

Post a Comment